Training, reflexes and anger flowed into Devon Caballero-Zarate the day he had an altercation with his ex-wife’s boyfriend, using his tattoo-smothered forearms to twist the man’s wrist, intent on breaking it.

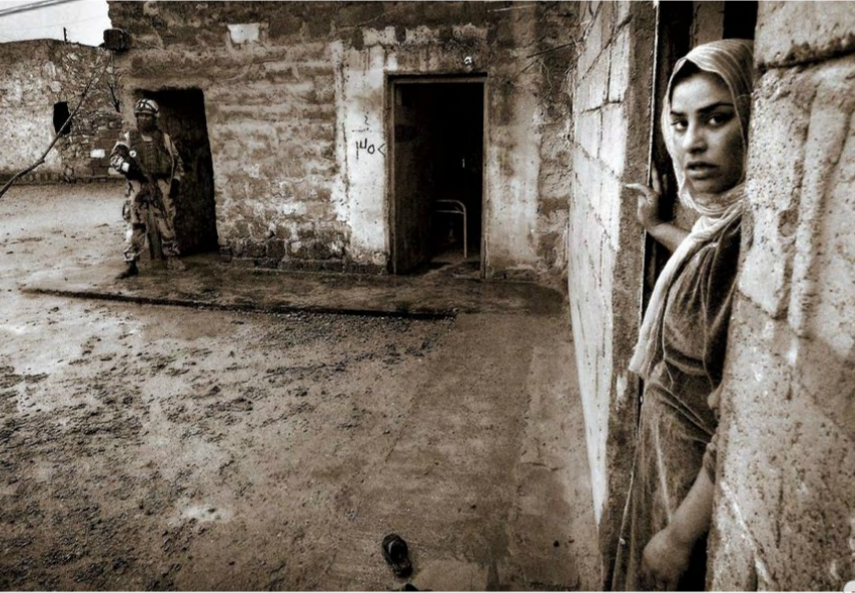

Fellow veteran Jordan Sherwood (right) talks with Mesa Community College student Devon Caballero-Zarate (left) about switching into a more suitable class.

“I just reacted,” Zarate recalled, saying he also smashed the boyfriend’s head into a car windshield before the Las Vegas Police Department showed up.

Zarate was a special purpose mechanic stationed in Kadena, Japan, from 2001 until 2003 when he was discharged. His post-service disabilities stem from non-combat related incidents, particularly the murder of his father while Zarate was serving overseas.

“I snapped… plain and simple, I snapped.”

His father’s death sent Zarate into a psychological state that his superiors thought gave enough reason to send him back home permanently, Zarate said.

He now studies at Mesa Community College, hungry to have his hands on a four-year degree in the near future.

“Being a soldier, the military, that was my world… that meant everything to me,” Zarate said.

Many student veterans, like Zarate, say their military experiences leave them feeling differently than other college students, and so they turn to organizations like the Student Veterans of America to help them.

SVA is a national organization with 883 chapters across the United States. These chapters assist veterans in their transition into the college environment, some of whom suffer from post-traumatic stress and are juggling school with demanding lives. They have families and some have jobs.

Jordan Sherwood, a former member of the SVA chapter at Mesa Community College, says there’s more to life for student veterans than “going to class for the day and then going home, calling up your buddies and partying… I mean there’s always that too,” he joked.

Veterans groups on campus are a place for these students to connect with other veterans.

The Veterans Club at Arizona State University, where Zarate attended school prior to MCC, provides opportunities for members to come together through community service, social events, one-on-one guidance, and political activism.

At an October ASU Tempe Veterans Club meeting, members congregated in the evening over a couple boxes of Papa John’s pizza. Its president, Walter Tillman, runs through his agenda in front of a dozen veterans, discussing political issues, community service and social events.

As a veteran, Tillman is active in Arizona politics and encourages members of the club to reach out to elected officials and voice their opinions about student veteran issues. Recently he worked with Congresswoman Kyrsten Sinema, a Democrat from Arizona, to push several bills that would further veterans benefits.

“It’s kind of in our best interest,” Tillman elaborated.

Joanna Sweatt is the Military Advocate at Arizona State University and is skeptical of mixing politics and veteran support. Sweatt is a U.S. Marine Corps veteran and works one-on-one with veterans that need assistance at school or who simply need some company.

“Politics are stressful, no matter how much passion you have for them,” she said.

Sweatt says that she sees more successful veterans emerge from support groups that focus on service and support.

MCC also has a significant veteran population. The MCC chapter president Brian Dozier says he prefers to focus on brotherhood.

Zarate, for example, missed three days of school after his altercation in Las Vegas. He had trouble communicating his situation to teachers and was able to go to Sherwood for help. Sherwood also happens to be an employee at the Office of Veteran Services at MCC. He took Zarate under his wing, helping him communicate to teachers his struggles. He also assisted in getting Zarate into more suitable classes.

“I’ve been there,” Sherwood said of Zarate’s situation.

Sherwood also served in the military and got himself through a two-year degree. He’s now working on a Bachelor’s degree. He says he understands the complicated scenarios of fellow veterans, adding that student veterans join the club to find help with exactly these scenarios.

“We’re all fighting the battle to assimilate back into civilian life,” MCC veterans club member Ted Morrison added.