The Scourge of Suicide

A News21 analysis shows veterans are taking their lives at twice the rate of civilians.

A News21 analysis shows veterans are taking their lives at twice the rate of civilians.

Veterans Come Home to Unprepared Nation

In the 12 years since American troops first deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq, more than 2.6 million veterans have returned home to a country largely unprepared to meet their needs. The government that sent them to war has failed on many levels to fulfill its obligations to these veterans as demanded by Congress and promised by both Republican and Democratic administrations, a News21 investigation has found.

Many of these combat veterans, returning from war with what will be lifelong illnesses and disabilities, are struggling to get the help they were promised in the form of disability payments, jobs, health care and treatment for such afflictions as post-traumatic stress disorder, traumatic brain injuries, physical disabilities and military sexual trauma.

Veterans who survived Taliban and al Qaida attacks, roadside bombs, mortar fire and the deaths of fellow soldiers told News21 that they have returned home to a future threatened by poverty, unemployment, homelessness and suicide. “The hardest thing you can ever do isn’t joining the military. It is hard,” said 30-year-old Luis Duran, a New Yorker who entered the Marine Corps after 9/11, deployed to Iraq and survived a suicide bomb. “The most difficult part is getting out.”

By far, the most vexing and public failure of the federal government has been its inability to distribute timely disability compensation to veterans with physical and mental injuries associated with their service – at a critical point in their transition home.

The News21 investigation found that as the lengthy backlog of delayed and mishandled claims began to surge dramatically, more than two-thirds of the claims processors in the Department of Veterans Affairs collected more than $5.5 million in bonuses.

Claims workers were effectively encouraged, based on a performance “credit system,” to process less-complex claims first, leaving to languish those claims involving multiple war injuries and missing paperwork.

Complex claims, the workers said, require calling and sending follow-up letters to veterans and requesting federal documents and medical records, all of which received zero points on the Veterans Benefits Administration performance evaluation for processors until December 2012, when the system was changed.

A local union representative for Boston claims processors, Roger Moore, said employees set aside complicated claims to preserve their jobs. “It’s like, ‘He’s gotta wait, because I have to get my numbers or my job is in jeopardy,’” Moore told News21.

Members of Congress continue to demand that the claims of the more than 500,000 veterans waiting more than 125 days be processed and paid, but so far the VA’s fixes have not cleared the backlog.

“They (soldiers) were put in these incredibly stressful situations and they also put their civilian jobs and education on hold, so it’s not like they win the lottery when they come back," said Rep. Tim Walz, D-Minn., of the benefits promised to veterans. “It’s meant to put them back on par with their peers, who had an advantage in the civilian sector while these men and women were gone.”

Large numbers of post-9/11 veterans are seeking treatment and compensation for post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury, considered nearly epidemic among those veterans. Both are widely claimed as an injury, and they are often difficult to assess and treat.

PTSD and TBI are “the two most prolific wounds coming out of the war,” said retired Gen. Peter Chiarelli, the vice chief of staff of the U.S. Army from 2008 to 2012 and now CEO of One Mind, a research and advocacy nonprofit for mental health and brain diseases.

“I have to be considered a horrible failure in my ability to get a handle on this problem,” Chiarelli said, noting the number of troops suffering from PTSD and TBI increased dramatically during his tenure.

Stephen Leon served two tours in Afghanistan and won the Army Commendation Medal for valor after a firefight with three suicide bombers outside a gate in Kabul in 2011. The blast from one of their bombs left him with wrist, neck, knee, back and ankle injuries, as well as traumatic brain injury and PTSD.

When he returned home July 2011, Leon couldn’t get his mind off Afghanistan, the battles and the friends he lost. “You’re used to a life of being at peace, with yourself and your family and having a nice time with your family, when you go over there all that breaks up,” he said.

More than a year later, Leon received his disability rating and compensation. Without it, he said he likely would be homeless or dead.

“It’s a waiting game” for veterans, said Mike Salois a regional executive director the Volunteers of America of Greater Ohio, which provides housing for homeless veterans in Ohio. “And when you particularly are already suffering from something on top of the disability, whether it be a mental illness or substance-abuse problem … they are not knowing how to cope with putting that off any more.”

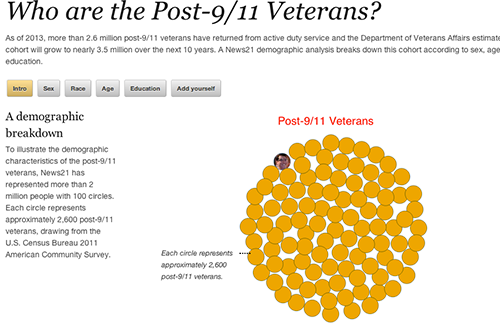

America’s post-9/11 veterans are the most diverse group of soldiers in the nation’s history, not only by race and gender, but by age, a News21 demographic analysis shows. They are overwhelmingly young, more than half were between the ages of 18 and 32.

By comparison, about 37 percent of the nonveteran population is over 50, and less than 29 percent of the nonveteran population is between the ages of 18 and 32.

This younger generation of veterans will count on the VA’s assistance to stabilize their lives and help them readjust for many years to come.

Veterans told News21 that the collateral consequences of PTSD, financial instability and other injuries associated with their disabilities sometimes triggered depression, anxiety, aggressive behavior and thoughts of suicide.

“All I ever considered when I thought about (suicide) was the guilt I was feeling and just wanting a way out, wanting to not have those memories anymore,” said Clinton Hall, 35, who served in Iraq and Afghanistan as an infantryman and now lives in Portland, Ore. His friend and fellow soldier killed himself shortly after returning home.

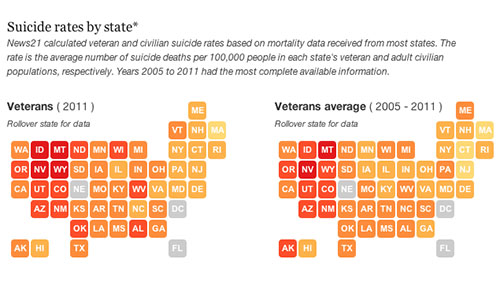

Despite intervention initiatives by the Department of Defense and VA, more than 49,000 veterans nationwide died by suicide between 2005 and 2011, according to state mortality data collected from 48 states by News21 in its eight-month investigation.

In every year over the last decade, the percentage of veteran suicides has significantly exceeded – usually by double or even triple -- the suicide rate of the general populations, the analysis shows. For example, Arizona’s 2011 veteran suicide rate was 43.9 per 100,000 people, more than three times the civilian suicide rate of 14.4.

Among states with the widest disparities and highest rates, Idaho had an average annual veteran suicide rate of 58.3 per 100,000 people, according to News21 analysis, compared to 22.8 for civilians. Montana had an average annual veteran suicide rate of 53 per 100,000 compared to 18.8 for civilians.

“(Veterans) have different rules and different expectations and ways of seeing themselves and their roles in society,” said Craig Bryan, research director at the University of Utah National Center for Veterans Studies. “What we see in society doesn’t always translate as well into the military.”

About 25 percent of post-9/11 veterans have been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, and 7 percent have traumatic brain injury, according to a Congressional Budget Office analysis of VA data. The average cost to treat them is about four to six times greater than those without these injuries, the CBO reported.

The post-9/11 veterans use the VA more than other veterans and their numbers are growing at the fastest rate, records show. Many will require care for the rest of their lives.

Yet, no government agency has calculated fully the lifetime cost of health care for the large number of post-9/11 veterans with lifelong ailments and disabilities. It is certain to be high, given the veterans’ survival rates, longer tours of duty, and multiple injuries.

They are veterans like Erik Castillo, who has been living with traumatic brain injury for nine years and goes to the VA three times a week for therapy. The shrapnel that entered Castillo’s brain from a bomb in Baghdad in 2004 burned a portion of his frontal lobe, which had to be removed. “I’ll utilize the VA for the rest of my life,” he said.

“Medical costs peak decades later,” said Linda Bilmes, a professor at Harvard's Kennedy School of Government and co-author of "The Three Trillion Dollar War: The True Cost of the Iraq Conflict."

Post-9/11 veterans cost the VA $2.8 billion in 2012, out of its total $50.9 billion health care budget for the year, records show. And that number is expected to increase by $510 million in 2013, according to the VA’s budget.

“And their needs will change as they age. And we don’t know with the TBIs and the multiple TBIs how those will evolve,” said Susan Lucht, program director of the VA Polytrauma Network Site in Tucson. “So VHA (Veterans Health Administration) is committed to doing lifetime care management for these injuries."

Women constitute an unprecedented 17.4 percent of the post-9/11 veteran cohort, more than twice the percentage of women in the overall veteran population, the News21 demographic analysis shows. More women will have served in Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan and Operation Iraqi Freedom than in any single previous conflict. More than a quarter of those women are black, almost twice the proportion found in the entire U.S. population.

Yet, these same women return to a nation that historically defines ‘veteran’ as male, which in the post-9/11 era has meant a lack of female-specific resources at VA facilities across the country.

“I think because the VA has dealt with men for so long, through all the previous wars, they’re not set up to handle females,” said Ohio Army National Guard veteran Crystal Sandor. “But we’ve been at this war for 10 years, it’s about time they figure it out.”

Though their numbers have been historic, with more than 280,000 women returning from deployments, female veterans said in interviews with News21 that they have trouble finding care and camaraderie within the VA services.

“I don’t think I’ve talked to one female veteran who goes to the VA who has had a good experience, that has been treated and received the care that they deserve,” Sandor said.

A 2013 Institute of Medicine report noted that, “Research on the health of veterans has focused on the health consequences of combat service in men, and there has been little scientific research . . . of the health consequences of military service in women who served.”

Some female veterans say this lack of understanding discourages them from seeking help at the VA, particularly for trauma from sexual attacks while in the military.

“Women already, so often, feel that they don’t belong in the military, either they’re not wanted or they have to prove to other people or themselves that they deserve to be there,” said Harvard psychologist Paula Caplan. “When you are traumatized and you’re devastated . . . then you think, ‘But I have military training, I’m supposed to be tough, I’m supposed to be resilient.’ ”

Jessie de Leon said she was raped while serving as an Army medic in Bamberg, Germany, from 2007 to 2009. Once back home in Florida, she said she found no comfort with therapists at the West Palm Beach VA and ended up at the Healing Horse Therapy Center with other female veterans in Loxahatchee, Fla.

“No one was forcing you to talk, nobody was saying you had to do anything,” de Leon said of the therapy center. “I didn’t realize you could gain so much confidence, gain so much self-motivation, get back your self-esteem, just by working with a horse, who never said a word to you.”

Women also are less likely to find a job than male veterans and more likely to be single parents with children to support, interviews and records show. In September 2012, the unemployment rate for post-9/11 female veterans hit a high of 19.9 percent before falling to 12.5 percent, three percentage points higher than the annual average for male veterans.

Employment - and underemployment - are issues for both men and women veterans in spite of highly visible efforts by Congress, state legislatures, businesses and philanthropists to push jobs initiatives. As of July, about 160,000 post-9/11 veterans of wars had not found work.

Job fairs, though highly touted and backed by the best of intentions, have had minimal success, according to data reviewed by News21. Hiring Our Heroes, a series of job fairs sponsored by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation, has helped fewer than 10 percent of participating veterans find work.

The Obama administration has prodded states to recognize military experience as sufficient for state licensing – certifying truck drivers, nurses and paramedics, among others. But most state licensing boards have so far delayed, forcing veterans to duplicate the training they received in their military jobs.

Sometimes, though, veterans who do get jobs can’t keep them, because of the residual effects of war or because their own failure to seek help interferes with their success.

“When I came back I was little torn up because we had lost one of our (explosive ordnance disposal) guys, the guy who was teaching us how to deactivate mines,” said Victor Nunez Ortiz, 31, who deployed to Iraq in 2004. “Around the same time, my great-grandmother who raised me passed away. I was notified when I was overseas. I was really sad most of the time, sad and angry towards the end of my deployment. When I came home I wasn’t able to let that go.”

“I wasn't able to hold my job, any job, for a year or longer,” said Nunez Ortiz. “The last time before I really realized that I needed to, like, seek help, I was the manager at Panera Bread. They let me go because they said I was a loose cannon.”

He began drinking, he said, and had a child, but no income.

“It became a roller-coaster ride of emotions,” he said.

Nunez Ortiz now lives in Massachusetts and works for Veterans Advocacy Services.

Retired Lt. Gen. Benjamin C. Freakley, an Arizona State University professor who is based in Washington, D.C., said most of the nation has little contact with the military since “the military represents just 1 percent of the population.”

“That means,” he told News21, that 99 percent of Americans “don’t know what a family is going through, don’t know what a military child is going through with a mom who deploys overseas … there’s a disconnection.”